Dual-Process Model of Bereavement (starts at 2.26 mins)

Loss is a theme that emerges frequently in the counselling room. This may be through death, or may involve the loss of other important parts of the client’s self and life, e.g. work, relationships or health.

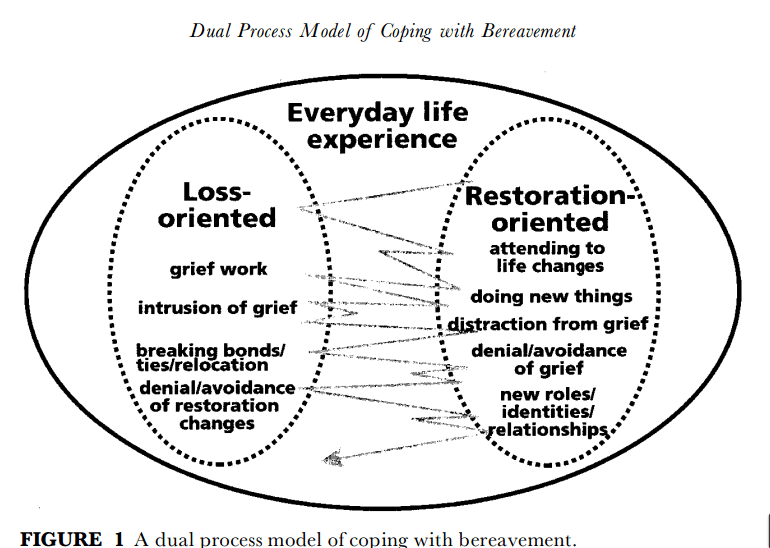

The dual-process model (illustrated below) was developed by researchers Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut. It is an oscillation model, showing the natural movement between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented behaviours in bereaved people.

Sometimes, people may get stuck in one or the other mode, or between the two modes. This causes them difficulty and means they are not grieving in an effective way. The model can help counsellors understand what is happening for a client, facilitating therapeutic work with them.

Some clients may present with recent loss, while others may have been bereaved a long time ago but have not been able to deal with this properly until now. Clients may be experiencing practical problems as a result of their loss. It is common to see feelings of loss in drugs and alcohol services, where stopping using the substance often leads to a sense of bereavement.

As a counsellor, you need to have looked at and worked through your own experiences of loss in order to be able to be there fully for bereaved clients.

You can watch a lecture on loss and bereavement by Rory here. The following video shows another model of grief: that of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

Hard-to-Help Clients (starts at 11.33 mins)

Rory believes that everyone has the capacity to change given the right conditions, but some clients can seem resistant to doing so or prone to demonstrate self-defeating behaviours. Possible reasons for this may stem from early life, for example:

- history of violence in the family

- protracted criticism in the past

- lack of emotional availability of carers as a child

- introjected values and conditions of worth

- unresolved issues relating to death and separation

- experiences of abandonment.

All these things can make it hard for the person to trust the counsellor, and may have led to attachment issues. Other possible reasons for certain clients being hard to help are that they may have unrealistic expectations about what counselling is and can do, difficulty in relating to others socially, or neurodiversity (e.g. Asperger’s).

Rory provides tips on working with hard-to-help clients, including the following:

- Be prepared to work hard to convince them that you are trustworthy.

- Take time to understand the client’s style.

- Contract carefully with the client about what is achievable.

- Look at yourself, asking whether you may be experiencing transference.

- Talk to your supervisor.

- Try hard to hang onto the idea that everyone can be helped.

Dementia and Validation Therapy (starts at 20.51 mins)

Can we do meaningful counselling work with people who have dementia? To answer this, it’s necessary to look at what you understand by the word ‘meaningful’. Bear in mind that not everyone comes to counselling in order to make changes; there is value too in simply being heard.

Carl Rogers’ six necessary and sufficient conditions for therapeutic personality change include a requirement for psychological contact; this may be difficult if the person is cognitively impaired. It is important to be sure that the client can give informed consent. Also, if you will need to liaise with medical staff, it is vital to cover this in contracting.

Validation therapy – developed in 1982 by social worker Naomi Feil (who came from Munich but grew up in a family home for older people in Ohio) – avoids ignoring or stopping what might appear to be irrational or illogical behaviour. Instead, it focuses on listening and on the objective here and now. The idea behind it is that if older people can express painful feelings, these will reduce; conversely, if these feelings are ignored, the pain will increase.